In 2001, the Jessamine County Historical Society helped to restore a historic family cemetery located in the county near the intersection of Highway 68 and KY 169. There are five identified graves in the cemetery according to the Society’s records.

The Remains

There are five headstones identified at the Russell Cemetery:

- Elizabeth McClanahan PREWITT (Dec. 13, 1787 – June 13, 1833)

- Harvey PREWITT (1786 – May 1840)

- Elizabeth Featherston RUSSELL, Age 80 years, Wife of Hezekiah (Unk – May 26, 1863)

- Hezekiah RUSSELL (April 10, 1790 – October 24, 1872)

- Lucy Ann SALE, wife of John (Feb. 15, 1822 – Sept. 2, 1858) [1][4]

The (Short) Backstory

The cemetery near the intersection of the two highways contains not just the Russell family remains, but it is a tangible reminder of history itself.

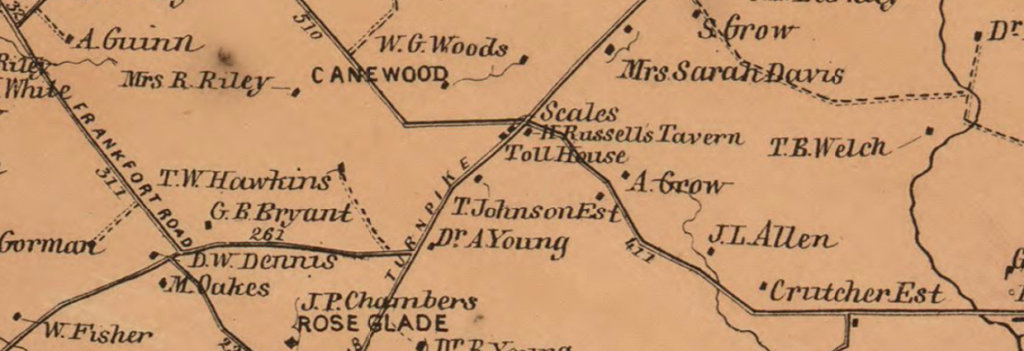

Russell’s Tavern at Russell’s Cross Roads

The map above shows a busy intersection at the onset of the Civil War. Near H. Russell’s Tavern was a tollhouse and scales where tolls were collected for those passing along the Lexington-Harrodsburg-Perryville Turnpike which was also known as Old Curd’s Road.

H. Russell’s Tavern was, of course, the tavern owned by Hezekiah Russell whose remains were buried at the Russell Cemetery following his 1872 death.

An archeological study conducted in the spring of 1999 uncovered “Hezekiah Russell’s mid-19th-century tavern and scales were also identified.” [2] The crossroads was historically referred to as Russell’s Cross Roads after the tavern.[3]

At some point before his death in 1840, Harvey Prewitt “operated the tavern at Russell’s Cross Roads.” Harvey Prewitt was born in 1786 in Halifax County, Virginia. His first wife, Elizabeth, is buried in the Russell Cemetery; they were wed in 1821. [5]

A Veteran of our Nation’s Independence

Harvey’s father, Byrd Prewitt, served in the Revolution, enlisting in Virginia “as a private in Capt. Henry Terrill’s Company, Col. Josiah Parker’s 5th Regiment.” [5] Byrd Prewitt served at the battles of Brandywine and Germantown. [6]

When he applied for a pension in the latter years of his life, he swore that he was “by occupation a farmer but from old age and infirmity can do but little that his wife is dead and that he now lives with his sons-in-law.” [7]

On July 4, 1794, Byrd attended a celebration at the nearby plantation of Colonel William Price; it was a gathering of veterans in the first celebration of our Nation’s independence to occur west of the Allegheny Mountains. [5]

Sources

[1] Russell Cemetery. Rootsweb. [Online] Rootsweb. [Cited: May 7, 2020.].

[2] Society for Historical Archeology. 1999. Current Research. [ed.] Norman F. Barka. SHA Newsletter. 1999, Vol. 32, 3, p. 14. [Online].

[3] Hudson, Karen E. 1999. Canewood Farm, Jessamine County, Kentucky.: National Register of Historic Places, 1999. #99000494.

[4] Russell Cemetery. Find A Grave. [Online].

[5] Prewitt, Richard A. Prewitt-Pruitt Records of Virginia. Des Moines: 1996 [Online].

[6] Bunch, Clyde N. 1999. Known Revolutionary War Soldiers of Jessamine County, Kentucky. [Online] January 11, 1999

[7] Prewitt, Byrd. 1828. Pension Application of Byrd Prewitt. [trans.] Will Graves. Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters. Lexington : 1828. [Online].

First, the

First, the

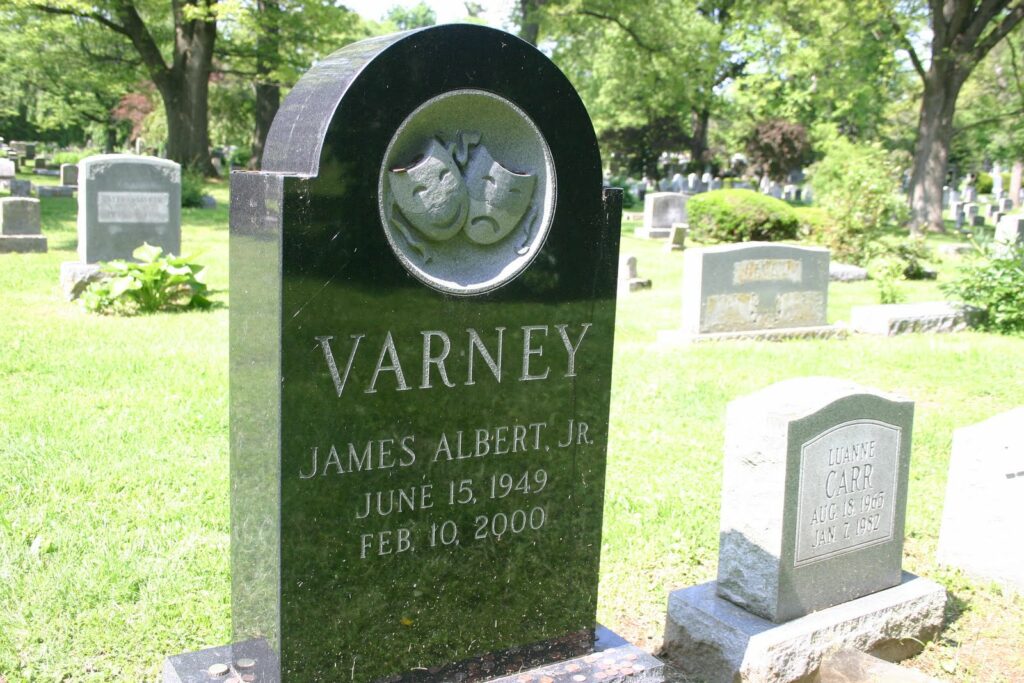

Ernest made his first appearance in an advertisement for Bowling Green’s Beech Bend Park in 1980. Ernest was just one of Varney’s many characters that usually found their way into Ernest movies or TV specials, of which there were more than a dozen. I absolutely LOVED Ernest movies as a kid, and while back I watched a couple of his movies again. I was shocked to discover that they’re still pretty funny as an adult.

Ernest made his first appearance in an advertisement for Bowling Green’s Beech Bend Park in 1980. Ernest was just one of Varney’s many characters that usually found their way into Ernest movies or TV specials, of which there were more than a dozen. I absolutely LOVED Ernest movies as a kid, and while back I watched a couple of his movies again. I was shocked to discover that they’re still pretty funny as an adult.