I was recently asked to preview a documentary which will air on Memorial Day on KET. It is called From Honor to Medal: The Story of Garlin M. Conner.

Memorial Day – Monday, May 25

8:00 p.m. on KET

“There are small towns hidden all over the United States…” begins this excellent production. It was a line that spoke to me as someone who loves our history and especially the untold backstories of our past.

From Medal to Honor is about two incredibly moving backstories. The description of Lt. Conner’s valor was emotional and did nothing less than illustrate his ultimate sacrifice. By all accounts, Murl Conner should have died on the battlefield; he survived and single-handedly saved hundreds of his fellow troops. The second story told in the documentary was the decades-long struggle to have the Medal of Honor bestowed upon this American hero.

I would encourage readers to celebrate Memorial Day by remembering Lt. Conner and watching this premier on KET.

Lt. Garlin Murl Conner

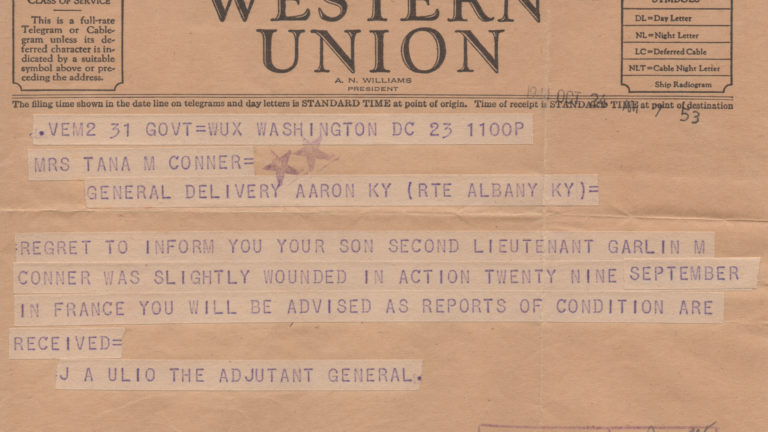

Born just months before the end of World War I, Lt. Garlin Murl Conner served as a technical sergeant and first lieutenant during World War II.

“On January 24, 1945, Lt. Conner committed an act of heroism so remarkable, and with so little regard for his own safety, that his commander, Major General Lloyd Ramsey, began paperwork for a Medal of Honor – the military’s highest combat award. Maj. Gen. Ramsey would never complete those papers. He was wounded himself, and still fighting through a bloody European campaign. Furthermore, Lt. Conner was soon heading home. So Ramsey got Conner what he could – the Distinguished Service Cross – figuring that Conner would apply for the Medal of Honor after the war.”

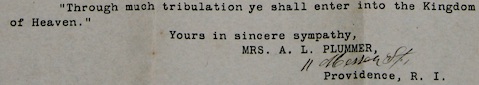

“Garlin Murl Conner never did. His generation was a humble one, and instead of seeking recognition, he settled into a quiet Kentucky life serving his community and helping veterans get the pensions and disabilities they deserved. By all accounts he lived a good life with his wife Pauline and his son Paul, and in 1998, at the age of seventy-nine, he died from Parkinson’s Disease.”

The Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor is the highest and most prestigious personal military decoration which can be awarded to members of the Armed Forces.

It is traditionally awarded by the President of the United States. In the case of Lt. Conner, the award was presented post-humously by President Trump in the East Room of the White House to Conner’s widow, Pauline.

Sixty Kentuckians have received the Medal of Honor. On this Memorial Day weekend, we honor all of those who served so valiantly and who gave their lives for the cause of freedom.

From Medal to Honor

On Memorial Day (Monday, May 25, 2020, 8:00 p.m. on KET), you’ll have the opportunity to learn about this American Hero. You’ll also discover about the half-century long struggle through government bureaucracy to finally bring the Medal of Honor the recognition he deserved.

The documentary film was sponsored by private donors as well as the Veterans Trust Fund of the Kentucky Department for Veterans Affairs. It was produced by UK’s Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, with director Al Cross serving as Executive Producer of this well-produced documentary.

Unattributed direct quotes, along with all images in this post, are from the film’s website, honortomedal.us.