|

| Projected paths of the I-75 Connector |

A Call to Action

A Call to Action

Take action and contact Ms. Curry with your opposition to Item No. 7-804, the I-75 Connector in Jessamine County.”

|

| Projected paths of the I-75 Connector |

A Call to Action

A Call to ActionTake action and contact Ms. Curry with your opposition to Item No. 7-804, the I-75 Connector in Jessamine County.”

|

| New Historic Marker in Jessamine County. Rep. Russ Meyer. |

Throughout Kentucky, roadside markers placed by the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet and the Kentucky Historical Society signify important historical sites. Approximately 2,450 of these markers have been placed at locations around Kentucky since 1949.

The first such historic marker, Ashland, is located in Lexington at the home of Henry Clay. Earlier markers had limited text compared to the lengthier modern markers, though the overall dimensions of the signs have not changed.

Over the last weekend in May, three new historic markers were placed at locales in Madison, Garrard and Jessamine counties. Each of these markers focused on the role of transportation during the American Civil War.

The Madison County marker recognized the decisive Confederate victory at the Battle of Richmond in August 1862 along the old state road, which was a major transportation route for moving Rebel troops.

In Garrard County, the new historic marker noted the movement of firearms authorized by President Abraham Lincoln to Camp Dick Robinson in the early years of the Civil War. There, regiments of Tennesseans loyal to the Union cause were enlisted.

|

| Camp Nelson National Cemetery. Author’s collection. |

The latest Jessamine County marker, marker number 2448, is the 19th marker to be located in Jessamine County. Many of these, including the latest addition, are located in and around Camp Nelson.

Marker 2448 reads in part, “When Camp Nelson was established in 1863, impressed slaves from local farms provided much of the labor to construct the earthen fortifications & improve the roads that brought men & materials to this supply base. The following year, when blacks were finally allowed to enlist, many of the former laborers became soldiers who trained at Camp Nelson.”

The African American enlistees served valiantly, often leaving behind their families in peril. Though many family members sought refuge at Camp Nelson, their encampment was only temporary, as they were eventually turned away during the cold winter of 1864. Nearly a quarter of the women and children forced to leave Camp Nelson perished.

In 1866, Camp Nelson National Cemetery was established and the site was added as a National Historic Landmark two years ago. There is no higher recognition that a site can receive, except designation as a National Park. An effort exists to turn Camp Nelson into a National Park, a move that would have major economic benefits for the county and region.

The addition of another roadside marker only serves to continue to tell the story of Camp Nelson’s importance to our local, state and national history.

And, as evidenced by the sheer number of historical markers around the commonwealth, there’s a lot of history to be told. There are new markers placed every year that tell even more of our shared history.

So go out and explore the history around you!

The post above was originally published in the Jessamine Journal on June 4, 2015.

The post above was originally published in the Jessamine Journal on June 4, 2015.

|

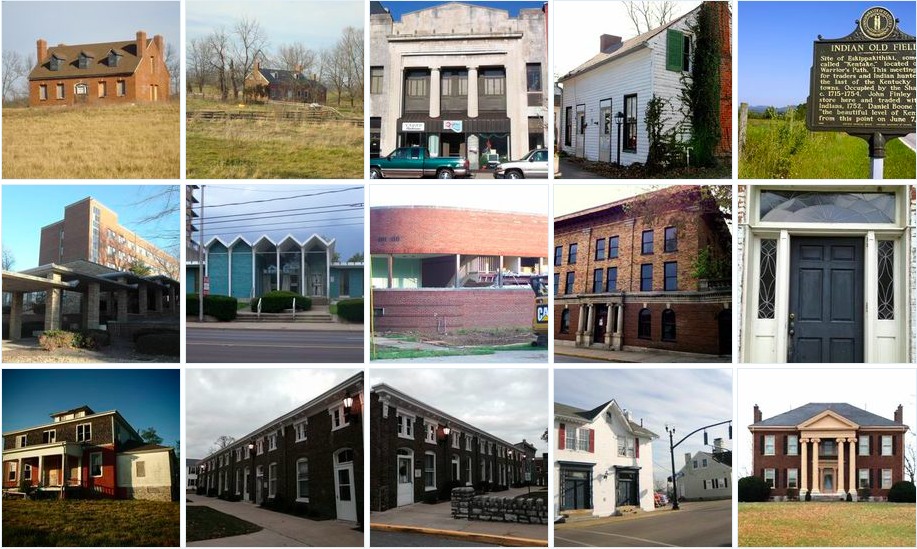

| Photographs of Select Sites on the Blue Grass Trust’s Eleven in Their Eleventh Hour List |

Each year, the Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation assembles a list of historic central Kentucky properties which are threatened. For the 2015 edition of the “Eleven in Their Eleventh Hour” list, the BGT has looked primarily beyond Fayette County to sites across 11 central Kentucky counties.

The list of counties largely resembles those included in the 2006 World Monument Fund’s designation of the Inner Bluegrass Region. The Blue Grass Trust included Madison County on its “11 Endangered List” while omitting Anderson County. All Kentucky counties, however, have “at risk” structures and deserve the attention of preservationists.

The BGT’s list is a great step toward recognizing that preservation can and should occur throughout Kentucky and not only in our urban cores. The 14 structures within the 11 counties also reflect that theme.

According to the BGT, “the list highlights endangered properties and how their situations speak to larger preservation issues in the Bluegrass. The goal of the list is to create a progressive dialogue that moves toward positive long-term solutions. The criteria used for selecting the properties include historic significance, lack of protection from demolition, condition of structure, or architectural significance.”

Both Cedar Grove and the Redmon House are architecturally significant houses from the early 19th century. The circa 1818 John & John T. Redmon House has a steep roof more often found in Virginia than Kentucky and has lost its original one-story wings. Though both buildings are vacant, they have undergone partial renovations recently and the BGT believes these structures could be still restored.

Mostly empty for two-plus years, the Citizens National Bank building at 305 West Main Street in Danville was built in 1865 with a double storefront that housed First National Bank of Danville and a drug store. Bank-owned and listed for sale, a demolition (or partial demolition) of this structure could affect adjacent structures with which the building shares walls. Dr. Polk House at 331 South Buell Street in Perryville sits across from Merchants’ Row and is arguably the historic landmark most in need of restoration in the downtown. Built in 1830 as a simple Greek Revival house with two chimneys and two front doors, the structure was purchased by Dr. Polk in 1850. A graduate of Transylvania University, he was the primary caretaker of wounded from the Battle of Perryville and his 1867 autobiography details the gruesome battlefield.

| Dr. Polk House in Perryville, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of the BGT. |

Indian Old Fields in Clark County was the location of Eskippakithiki, the last known Native American town in what became Kentucky. Located on Lewis Evans’ 1755 map of Middle British Colonies, this highly important site was significantly impacted during construction of a new interchange (which opened September 2014) for the Mountain Parkway crossing KY 974 near the center of the Indian Old Fields.

The Kentucky Heritage Council noted in 2010 that “’Indian Old Fields,’ is a historic and prehistoric archaeological district of profound importance,” with 50 significant prehistoric archaeological sites identified within 2 kilometers of the interchange. These sites cover the Archaic Period (8000-1000 BC), Woodland Period (1000 B.C. -1000 AD) and Adena Period (1000-1750 AD), with several listed on the National Register of Historic Places. These include villages, Indian fort earthworks, mounds, sacred circles and stone graves. The site also has substantial ties to the famous Shawnee Chief Cathecassa or Black Hoof, Daniel Boone, and trader John Finley.

With the new $8.5 million dollar interchange now open, there are significant concerns that these sites with be under threat from pressure to further develop the area.

The Blue Grass Trust’s 2014 “Eleven in Their Eleventh Hour” focused on the historic resources at the University of Kentucky. Many of those included on the list (and most of those demolished) were Modern buildings designed by locally renowned architect Ernst Johnson. Research into Johnson’s work by the BGT and others such as architects Sarah House Tate and Dr. Robert Kelley was joined with education and advocacy programming focused on his architecture and legacy as a master of Modernism. This research and programming led to other efforts by the Blue Grass Trust, namely working to educate the public on the historic value of mid-century architecture.

In our continued education and advocacy effort surrounding these structures, the Blue Grass Trust lists Fayette County’s mid-century Modern architecture as endangered. Often viewed as not old enough or not part of the traditional early fabric of Lexington and surrounding areas, the Modern buildings of the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s are being substantially and unrecognizably altered or demolished. It is important to recognize that buildings 50 years of age are eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, a length of time deemed appropriate by the authors of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 for reflection on an era’s importance. Read more from the Kaintuckeean’s earlier post on the People’s Bank branch on South Broadway.

%2BBank%2B(Photo%2Bby%2BRachel%2BAlexander).jpg) |

| People’s Bank in Lexington. Photo by Rachel Alexander. |

Both the Old YMCA in downtown Frankfort faces potential demolition and the Blanton-Crutcher Farm in Jett are slowly deteriorating from neglect and both structures are worth saving. The 1911 Old YMCA at 104 Bridge Street in Frankfort, designed in the Beaux Arts style by a a Frankfort architect, was a state-of-the-art facility featuring a gymnasium, indoor swimming pool, bowling alley, meeting rooms and guest quarters. While a local developer is hoping to transform it into a boutique hotel, there is also a push by the city of Frankfort to demolish this structure. If saved, this could be a transformative project in our capital city.

The Blanton-Crutcher Farm in Jett includes an architecturally and historically significant circa 1796 house built by Carter Blanton, a prominent member of the Jett farming community. In 1831, Blanton sold the farm to his nephew, Richard Crutcher, the son of Reverend Isaac Crutcher and Blanton’s sister, Nancy Blanton Crutcher. The 1974 National Register nomination for the farm notes: “The Crutchers were excellent farmers. Three generations of the family farmed the land and made improvements on the house until 1919 when the property was sold. It has remained a working farm with a large farmhouse, at its center, that has evolved over 180 years of active occupation.” In the 1880s, Washington Crutcher significantly increased the size of the house, turning it into the Victorian house that stands today (although the porches were removed due to deterioration and other modern features have been added).

The Handy House, also known as Ridgeway, is located on US 62 in Cynthiana, KY. The nearly 200-year-old house was built in 1817 by Colonel William Brown, a United States Congressman and War of 1812 veteran. The farm and Federal-style house were also owned by Dr. Joel Frazer, namesake of Camp Frazer, a Union camp during the American Civil War. In the 1880s, the house underwent significant renovations by W. T. Handy, the owner from 1883-1916 and for whom the house remains named.

The Handy House checks almost every box when it comes to saving a structure: an architecturally and historically important house in good enough shape to rehabilitate, a listing on the National Register of Historic Places, qualification for the Kentucky Historic Preservation Tax Credit, and a group, the Harrison County Heritage Council and a descendant of the original owner, willing to take on the project. Unfortunately, the Handy House is jointly owned between the city and the county. County magistrates voted to tear it down, and the city opted not to vote on it with the hopes that the new council will come to a deal with the Harrison County Heritage Council, which has offered to purchase and restore the house as a community center. Read more from the Kaintuckeean’s earlier post on Ridgeway.

Completed in 1881, Nicholasville’s Court Row is located right next to the Jessamine County Courthouse. Italianate in design and largely unchanged exterior-wise, Court Row is one of the most significant and substantial structures in downtown Nicholasville.

In a broad context, the listing of Court Row is a comment on the status of all the historic resources in downtown Nicholasville. Several threats exist that are culminating in drastic changes to the fabric of the town. Foremost, Nicholasville failed in 2013 to pass its first historic district, an overlay that would have encompassed the majority of the downtown and helped to regulate demolition and development. Then, within the past month, two historic structures were demolished, including the Lady Sterling House, an 1804 log cabin very close to the urban core. Additionally, Nicholasville is on the ‘short list’ for a new judicial center, the location of which has yet to be determined but will almost certainly have an effect on the downtown. Together, these threats present the potential for the loss of significant portions of Nicholasville’s charming downtown.

Preservation has had a lot positive movement in Richmond. The Madison County Historical Society is active; the beautiful Irvinton House Museum is city-owned and the location of the Richmond Visitor’s Center; and the downtown contains a local historic district. Like most local historic districts (also known as H-1 overlays), though, the Downtown Richmond Historic District protects historic buildings and sites that are privately owned. That means that city- and county-owned sites are exempt from the H-1 regulations.

The potential damaging effects of this can already be seen. In February 2013, downtown Richmond lost the Miller House and the Old Creamery, two of its most historic buildings. Both were in the Downtown Richmond Historic District and on the National Register of Historic Places. Owned by the county, the buildings were demolished with the hopes of constructing a minimum-security prison on the site that would replicate the exterior façade of the Miller House, according to Madison Judge/Executive Kent Clark. There are several other historic sites in the urban core that are owned by either the city or the county, leading to worry about the state of preservation in Richmond’s downtown.

Built circa 1850 by David W. Thompson, Walnut Hall is one of Mercer County’s grand Greek Revival houses. A successful planter and native of Mercer County, Thompson left the house and 287 acres of farmland to his daughter, Sue Helm, upon his death in 1865. In 1978, Walnut Hall was listed on the National Register of Historic Places along with two other important and similar Mercer County Greek Revival houses: Lynnwood (off KY Highway 33 near the border of Mercer and Boyle Counties) and Glenworth (off Buster Pike).

The James Harrod Trust has notified the Blue Grass Trust that the house may be under threat of demolition, as it is owned by a prominent Central Kentucky developer known to have bulldozed several other important historic buildings.

Located in Blue Springs, KY, off Route 227 near Stamping Ground, the Choctaw Indian Academy was created in 1818 on the farm of Colonel Richard M. Johnson, who served as Vice President of the United States under Martin Van Buren (1837–1841). The Academy was created using Federal funding and was intended to provide a traditional European-American education for Native Americans boys. (It was one of only two government schools operated by the Department of War – the other being West Point.) Originally consisting of five structures built prior to 1825, only one building – thought to be a dormitory – remains. By 1826, over 100 boys were attending the school, becoming well enough known to be visited by the Marquis de Lafayette in 1825. The school was relocated to White Sulphur Springs (also a farm owned by Colonel Johnson) in 1831. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. Read more about the site from the Kaintuckeean’s earlier post on the Choctaw Indian Academy.

.jpg) |

| Remaining structure of Choctaw Indian Academy. Photo by Amy Palmer. |

Located on the corner of Maple Street and Lexington Pike in Versailles, the Versailles High School is a substantial structure built in 1928. The building operated as a high school for 35 years before becoming the Woodford County Junior High in 1963, operating as a middle school until being shuttered in 2005. After 77 years of continuous operation, the building has been empty for nearly 10 years.

With no known maintenance or preservation plan, concern exists that the historic Versailles High School will deteriorate from neglect and, ultimately, be demolished.

You can learn more about the Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation on its website, www.bluegrasstrust.org.

|

| Our Campsite at “Sycamore Hollow” at Fort Boonesborough State Park. Author’s Collection. |

It wasn’t until earlier this summer that I attempted camping for the first time. At the urging of the now six-year-old Lil’ Kaintuckeean, we pitched a borrowed tent in the back yard. Despite the storm that night, our rain fly kept us dry and we both managed to stay through the night in the backyard tent. All much to my wife’s surprise.

More recently, I endeavored to take the Lil’ Kaintuckeean and his Lil’er Sister on an overnight camping trip … away from home.

Along with a friend and one of his progeny, we found the destination of the primitive camp grounds at Fort Boonesborough State Park. Tents were pitched under the protective state historic marker, “Sycamore Hollow.” Although the roadside markers traditionally are found only roadside, here was one in the center of our campground!

The area surrounding this marker was known as “Sycamore Hollow.” Daniel Boone and his small gropu camped here ca. April 1, 1775, and began construction of rough log huts. When Col. Richard Henderson arrived on April 20, 1775, fear of flooding caused him to have the location of the fort moved 300 yards to higher grounds.

We ran no risk of flooding during our dry stay, but it was an incredible feeling to camp on the very same steps where Daniel Boone once laid his head.

Of course, at Boonesborough, history is everywhere. The fort was the first town chartered in the Kentucky territory, in an act by the Virginia legislature in October 1779. It was established in 1775 by the Transylvania Company, the North Carolina outfit established by Richard Henderson. The Transylvania Company hired Boone to lead the expedition into the Kentucky wilderness.

|

| Illustration of Fort Boonesborough in 1778. George W. Ranck, 1901. |

In was on the banks of the Kentucky at Boonesborough that Boone’s daughter, Jemima, as well as the Callaway girls were kidnapped by an Indian raiding party and later rescued.

|

| The Kids Enjoying Fort Boonesborough in Madison County. Author’s Collection. |

Fast forward to 1974. In that year, the Commonwealth opened the recreated fort a short distance from where the original fort once stood. Now in its 40th year, the recreated fort remains in excellent condition and is well-operated for those visiting to learn of Kentucky’s history.

I hadn’t been to Fort Boonesborough since probably the fourth grade, but I found the living history museum to be engaging and utterly fascinating. Three settlers’ homes were laid out so that one could see how the settlement evolved with comforts being added over time. Craftsman were on hand to explain to adult and child alike the intricacies of gunsmithing, woodworking, and other trades.

|

| Walking the Trails at Boonesborough. Author’s Collection. |

And of course, the trails between campsite and fort made for great adventure!

Although we could certainly endeavor to improve our creature comforts at the campsite, the two kiddos and I had a successful and fun weekend of camping and exploring Kentucky’s early history. The campgrounds and fort are open year round, though the fort is only open on the weekends beginning November 1 (winter hours).

Like most of Kentucky, Fort Boonesborough is time well spent!

|

| Marquee for the historic Lyric Theater – Lexington, Ky. |

The seats at the historic Lyric Theatre in downtown Lexington were filled with people concerned and opposed to the “Vampire Road,” a nickname for the proposed I-75 Connector between Nicholasville and the interstate in Madison County. “Off the Road!” was a fantastic rally featuring an incredible collection of Kentucky artists united “to celebrate Kentucky and oppose a proposed I-75 Connector road.”

|

| Barbara Kingsolver at the Lyric Theatre, Sept. 19, 2013. |

Barbara Kingsolver, author and Nicholas County native, explained why she was there. “I’m such an advocate of the little wild places. The little places you can go again and again. They help you become stronger, truer, better people.”

She juxtaposed these “little wild places” as being as critical to our national psyche just like the bigger wild places such as the Grand Canyon or Yellowstone that we’ve made efforted so hard to protect.

Perhaps this is because, as poet Eric Scott Sutherland remarked: “We find the muse in nature.”

A collection of Guy Mendes photographs opened earlier in the evening at the Ann Tower Gallery at the Downtown Arts Center. Mendes’ photography captures the essence and emotion of “Marble Creek Endangered Watershed” which is one of these “little wild places” which would be forever destroyed by the construction of the Vampire Road. The Mendes collection will remain on display until November 3.

The Vampire Road exists because this proposed road has been proposed on multiple occasions, but “the plan just couldn’t be killed” according to the lyrics of the Steve Broderson and Twist of Fate song, The Vampire Road. The music video was first shown at last night’s event. And you can watch it here on the Kaintuckeean!

Legendary Kentucky author Wendell Berry delivered a delightful resolution from the fictitious Buzzard General Assembly which gave a humorous yet serious sense of what is at stake. Berry stated that the Assembly “unanimously concluded and instructed me to tell you that they foreswear all rights and claims to the carrion, with the giblets and gravy thereof, that would be produced by said connector.” The buzzards seem to prefer the more diverse palate offered in nature rather than on pavement.

Richard Taylor, a former Kentucky poet laureate remarked on Kentucky’s pioneer spirit which helped us forge into the wilderness in centuries past only to suggest that “it is time to give up our pioneer mindset to conquer and to consume.”

Professor Maurice Manning took a different, more spiritual tone: “I believe God made the world we live in. And destroying it is a sin.”

“I know not what course others may take; but as for me Give me Liberty, or give me Death!”

Patrick Henry’s famous oratory has been a call to freedom since he uttered those words before the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1775. Henry would go on to serve as the governor of Virginia from 1784 to 1786.

During this time, he signed a “perpetual and irrevocable” charter for the operation of a ferry boat in favor of John Craig. The ferry would cross the Kentucky River between Fayette and Madison Counties near the mouth of Tate’s Creek.

In 1798, Jessamine County was created from Fayette County with a portion of the boundary being along Tates Creek road to the Kentucky River. The General Assembly clarified the boundary in 1868, so that it would “run with the center of the said turnpike road leading from Lexington to the Kentucky River.”

It can thus be said that one headed southbound on the ferry departs from Jessamine, but those arriving on a northbound trip would arrive in Fayette.

From either direction, passengers on the ferry might pick up on the historical cues flying overhead. The vessel, aptly named the John Craig after the first ferry operator, carries four flags. The American, the POW-MIA and the Kentucky flags wave alongside the flag of Virginia under whose charter Valley View remains operational.

Few passengers in the 350 vehicles ferried daily probably consider the history of the ferry. For commuters, it is simply a vital shortcut between Richmond and Lexington or Nicholasville. For the tourists who often travel the ferry, the focus is on the nostalgic crossing itself.

Federal regulations imposed in 2006, however, are making it harder for the oldest continually operated enterprise in Kentucky to continue, since the operator must be a captain licensed with the United States Coast Guard.

Licensure can take four to six months and cost about $2,000. This makes it difficult to find a replacement captain when one resigns.

The John Craig has no steering capability and is tethered to overhead guide cables which are used to maneuver the vessel across the 500-foot stretch of river. Valley View isn’t the Staten Island Ferry or one of those crossing Washington state’s Puget Sound.

Yet it is snared into the bureaucratic red tape designed for these large ferries which sail on open waters. The regulations are a one-size-fits-all misfit threatening the Valley View Ferry’s own existence.

And while it seems that the Valley View Ferry Authority has secured a new captain which will, in due time, allow a return to normal hours of operation, the remaining existence of these federal regulations remain as a long-term threat.

That’s why U.S. Rep. Andy Barr (R-Lexington) introduced H.R. 2570, the Valley View Ferry Preservation Act of 2013, exempting the John Craig from Coast Guard licensure requirements.

The bill requires Kentucky to establish licensing requirements sufficient to protect ferry passengers.

In other words, the Preservation Act simply returns regulatory authority over the Valley View Ferry to the state.

Certainly, Patrick Henry would have been pleased with the Preservation Act. He was an ardent supporter of state’s rights who even declined to attend the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Henry feared that the federal government would become its own monarchy leaving little room for the individual States.

Allowing Kentucky to license the John Craig, while still leaving the vessel open to Coast Guard inspection, is a common sense solution critical to keeping America’s third oldest ferry operation afloat long into the future.

This column originally appeared in the Jessamine Journal.

It should not be republished without permission.

“Oh Captain, my Captain” wrote Walt Whitman in a poem having nothing to do with seafaring. Today, however, we look for a captain for an inland vessel: the John Craig.

Craig, the original ferry operator at Valley View, received his charter to operate from Virginia Governor Patrick Henry. Today, the ferry crossing the Kentucky River bears his name as it carries 350 vehicles daily between Fayette/Jessamine and Madison Counties.

Two captains have steered the vessel across the docile Kentucky, but one of the captains is retiring. Since January, the Valley View Ferry Authority has looked for a local, qualified replacement to no avail.

As a result, the ferry will be forced to stop weekend service and reduce weekday hours. This is a blow to this historic Kentucky institution – the oldest continually operating enterprise in the Commonwealth.

If you know of a qualified cap’n, let them know about this job opening!

(h/t: H-L)

UPDATE: Valley View Ferry Authority has hired a new captain to replace the retiring one. Once training is complete, normal operating hours for the Valley View Ferry will resume. [Jessamine Journal]

Since 1999, the Blue Grass Trust has created an annual list of “Eleven [historic properties] in Their Eleventh Hour.” Each property is selected on the following criteria: historic significance, proximity to proposed or current development, lack of protection from demolition, condition of structure, and architectural significance.

The BGT’s goal of highlighting these properties is to find long-term solutions to preserve them for generations to come.

In no specific order, the BGT has announced this year’s “Eleven in Their Eleventh Hour” this morning at the Hunt-Morgan House.

|

| Carriage House – Madison County, Ky. |

When driving through Madison County earlier this year, I was struck by the number of “destinations” along U.S. 25 south of Richmond. Historic markers abound, a military complex is imposing, and this abandoned carriage house stands as a reminder of days gone.

I’ve previously written a series on the carriage houses of Lexington’s Gratz Park (series pts. 1, 2, and 3), but unlike those urban instances this carriage house appears in a rural setting. Although I cannot find any specifics on this carriage house at this time, I am hopeful that readers might fill in the gaps.

The carriage house is situated off a small private road adjacent to US25 (Berea Road), formerly the eastern portion of the Dixie Highway. It is probable that the private road was the original Dixie Highway and that the carriage house opened directly upon it. With two stories and large windows above each of the carriage ports, it is likely that living quarters were included above. The stately stone entrance to the drive reveals no great manor behind, likely the home to which the carriage house belonged has been lost to the annals of history. (Any help on the history here… por favor?)

Amazingly, the only reference to this carriage house I can find online comes from the Madison County Quilt Trail as the Star Shadows barn quilt can be seen behind the carriage house.

Oh… and check this out: I’ve added Lightbox to the blog.

|

| Bluegrass Army Depot – |

Occasionally, it makes the news because of a gas leak or new attempts at environmental remediation. But the Bluegrass Army Depot, which is little known to most Kentuckians, occupies a massive, secretive 15,000 acre tract in Madison County.

The Blue Grass Ordnance Depot in Madison County was announced by Washington in the summer of 1941 and, by early 1942, the government was filing condemnation actions against landowners who did not sell their land through private sale. In October 1942, the facility began storage of its first munitions. Even after World War II, the BGOD remained a critical facility.

In 1964, the role of the Lexington Army Depot (fka Lexington Signal Depot) at Avon was deminished and its operations were merged into the Madison County facility which was then-renamed the Lexington-Bluegrass Army Depot. In 1992, army reorganization caused the name to again be changed to simply the Bluegrass Army Depot. The old Lexington depot was formally BRAC’d in 1995; it has been converted to a light industrial park “Bluegrass Station” near I-64 and KY-859.

Since 1944, BGAD has housed about 2% of America’s chemical weapons stockpile. That’s right… near Richmond sits over 500 tons of VX, sarin, and mustard agent. A couple of leaks in the past decade have made some nearby residents understandably nervous; they await tornado-warning-like-sirens to notify them of the need for evacuation. Congress, however, has set a 2017 deadline to eliminate the stockpile in compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention which has been agreed to by 65 countries.

Since 1944, BGAD has housed about 2% of America’s chemical weapons stockpile. That’s right… near Richmond sits over 500 tons of VX, sarin, and mustard agent. A couple of leaks in the past decade have made some nearby residents understandably nervous; they await tornado-warning-like-sirens to notify them of the need for evacuation. Congress, however, has set a 2017 deadline to eliminate the stockpile in compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention which has been agreed to by 65 countries.

The military conducts other operations at BGAD as well, including military equipment design and (of course) storage. Other secretive operations are also rumored to exist on the sprawling facility: alien technology, UFOs, undisclosed stealth technology and more.

But from the road on a clear day, it seems to be just a beautiful verdant field behind “US Army Property – No Trespassing” fencing.