Each week, the National Park Service transmits a list of properties added to the the National Register of Historic Places. Depending on applications pending, there are weeks where no Kentucky properties are listed for inclusion. Some emails are full of Kentucky’s rich history. Such was a recent e-mail.

As I alluded to in one of my weekly roundup’s last month, two Kentucky properties were designated as National Historic Landmarks. This designation is the highest designation that can be afforded a property in terms of historic significance. With the inclusion of the George T. Stagg Distillery in Franklin County and the Camp Nelson Historic and Archeological District in Jessamine County, the number of Kentucky properties designated as National Historic Landmarks rests at thirty-two.

|

North elevation of the Liggett and Meyers Harping

Tobacco Storage Warehouse, Source: NRHP App./KHC |

From Lexington, the Liggett and Meyers Harpring Tobacco Storage Warehouse (1211 Manchester Street) was added to the Register. Constructed in 1930, the warehouse sits on a six acre tract and was well-situated to tobacco storage. A rail spur from the L&N railroad ran to the property and, as preferred shipping methods changed, proximity to New Circle Road kept the Liggett and Meyers building relevant. The building itself is constructed in six segments with each segment containing 20,000 square feet. This immense structure was important to an industry vital to central Kentucky. Today, the building is part of the city’s growing Distillery District.

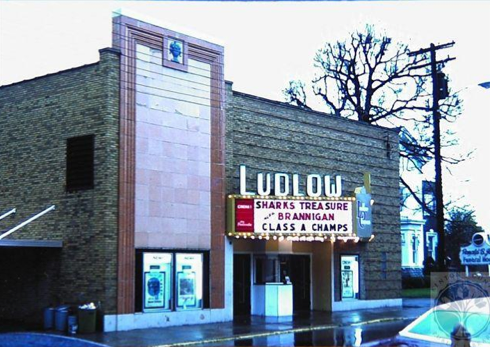

The Ludlow Theatre, 322-326 Elm Street, is in the community of Ludlow in Kenton County. The Ludlow Historic District, added to the National Register in 1984, already includes the ca. 1946 theater, but the Ludlow Theatre is now individually listed. Of course, in 1984 the Ludlow Theatre (then less than 50 years of age) was deemed a non-contributing structure, yet the passage of thirty years has changed perspective. Consistent with much of the architecture built in the mid-twentieth century, the Ludlow Theatre is “largely a modest modern building

with little to characterize it within a specific style.” Architectural interest is found in the façade, however, as every sixth of the variegated brick projects slightly from the façade. The most significant change to the building’s exterior since 1946 is the removal of the marquee. This occurred around the time of the historic district’s inclusion on the Register, but can be more readily attributed to the theatre’s closure in 1983.

As Nate wrote, “There is no legitimate reason why anyone would ever stumble upon Hindman.” Though, remarkably, the National Register application remarks that “few Kentucky counties can match the education, literary, cultural, and political heritage found in and near Hindman.” With credits like that, one can imagine the variety of architectural styles found in the district. Much can be credited with three of the earliest Appalachian Settlement Schools being established in Knott County. So if one were to stumble into Knott County’s seat, they would find the sixty-one buildings in the Hindman Historic District, of which 40 are deemed to be contributing. They consist of religious, governmental, residential, commercial, educational, and health care purposed structures, though the majority are two-story residences and commercial structures built between 1903 and 1960. After this period, however, many older structures have been significantly altered or demolished and this has diminished the historic character of the community.

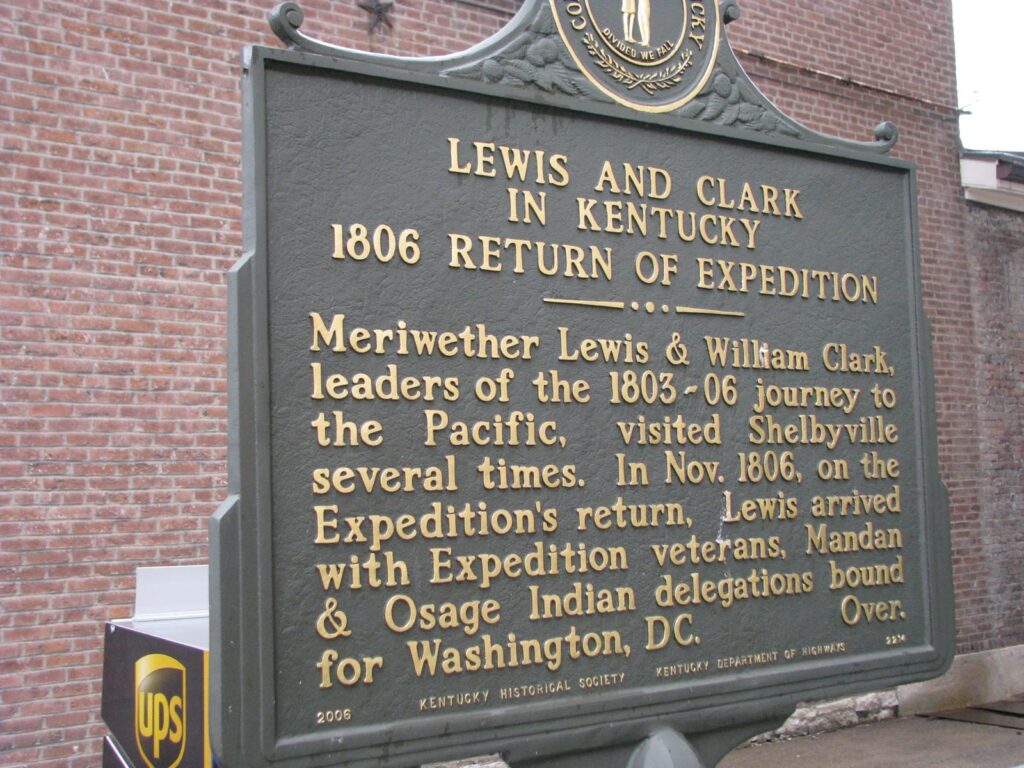

Finally, the Buck Creek Rosenwald School in Finchville was constructed ca. 1920 as a one-room school house and was adapted into a residence in 1959 (the school had closed in 1957). One story with hipped roof, this simple structure was a Rosenwald school for African American children during the years of segregation. It was one of only two Rosenwald schools in Shelby County. Two contributing buildings – an outhouse for either sex – are also mentioned in the National Register application. The application also contains accounts of the school day from former students – a fascinating read! More fascinating is that the application was the project of Girl Scout Julia Bache in pursuit of her Girl Scout Gold Award. Well done, Julia!