The Kentucky Military Heritage Commission, until recently, was a little-known state agency. Over the past week, the Commission has received quite a bit of news, both locally and nationally, as Lexington considers what to do with two statutes presently standing in the public square.

Yesterday’s unanimous vote by the Lexington-Fayette Urban County Council was to “support the relocation” of the two statutes, a decision that will ultimately be made by the Kentucky Military Heritage Commission.

The Statues

The two statues at issue are of John C. Breckinridge and John Hunt Morgan. Both men were slaveowners who took up arms against the United States during the Civil War. Both men came from prominent, white Lexington families who were instrumental in Lexington’s 19th century growth and prominence (that familial success being achieved largely through the involuntary toil of slaves owned by the respective families).

Said one woman speaking to the LFUCG Council before their unanimous vote on August 18, 2017, “[Breckinridge and Morgan’s] only claim to fame is treason against this country.” Well, here’s a little more about the two men and the monuments that have stood for more than a century in the heart of Lexington…

John C. Breckinridge

Breckinridge was a Lexingtonian, a Vice President of the United States under President Buchanan, and then a U.S. Senator from Kentucky. But Breckinridge was expelled from the Senate upon joining the Confederate Army in 1861. He received a commission as a brigadier general; on February 7, 1865, Breckinridge would become the final Secretary of the Army for the Confederate States of America.

In The Breckinridges of Kentucky, James Klotter (the state historian since 1980) described Breckinridge’s fate in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. By June 1865, the majority of the Confederate cabinet, including Vice President Stephens and President Davis, were captured and imprisoned. “Breckinridge determined early that he would not suffer such a fate.” Klotter writes of the Breckinridge’s escape from capture:

What followed enhanced the Breckinridge legend and surrounded an already appealing figure with even more romance. Here was a daring, charismatic Southern leader fleeing from Union pursues. Swarms of mosquitoes, ticks, sand-flies, and other insects of every description tormented him as he fled through Florida. In a boat too small to lie down in, the party rowed along the rivers of the area for days. Alligators surrounded them; rain soaked their food; hunger reduced them to eating turtle eggs, sour oranges, green limes, and coconuts. … Needing a larger boat to cross to Cuba, the “sailors” commandeered at gunpoint a larger craft. … The sloop No Name sailed into Cardenas, Cuba, on 11 June 1865. General Breckinridge – bronzed, unshaven, his feet swollen by salt water but the long mustache still intact, wearing a blue flannel suit open at the neck and an old slouch hat – was welcomed as a conquering hero.

John Cabell Breckinridge remained on the lam through the remainder of the 1860s until after President Johnson had issued him amnesty; Breckinridge died in 1875. The statue commemorating Breckinridge was erected by the Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1887 in the middle of Cheapside Park. In 2010, the statue was relocated so that it fronted Main Street making space for the Fifth Third Bank Pavilion. The bronze statute rests upon a granite pedestal, with each “being of equal height” according to the 1997 National Register nomination form.

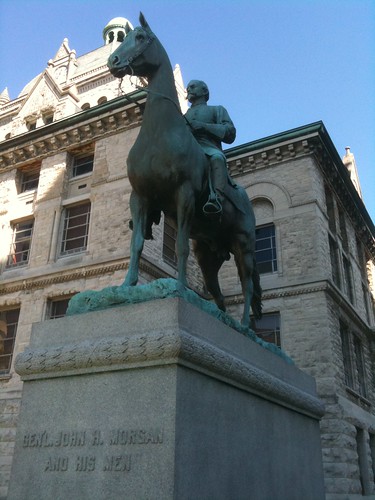

John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan was born in Alabama, but his mother was raised in Lexington before marrying an Alabaman. John Hunt Morgan returned to Lexington for two years as a student at Transylvania before being suspended for dueling. During the Mexican War, Morgan achieved the rank of lieutenant in the United States Army.

John Hunt Morgan is best known, however, as the “Thunderbolt of the Confederacy.” He joined the Confederate Army in early 1862, and, following the Battle of Shiloh, began a series of raids. His raids were intended to disrupt Union supply lines and communications. His guerrilla tactics had as much, if not more, effect on citizens as it did on Union forces. In one raid, much of Cynthiana was burned. Morgan’s actions were unauthorized and, in 1864, he was killed by Union troops during a raid in Tennessee. Some persuasively argue that his death was akin to “suicide by police,” as he desired to neither be captured by Union forces nor court martialed by the Confederacy.

Hopemont, now known as the Hunt-Morgan House, was the home of Morgan’s maternal grandfather, John Wesley Hunt; it was built in 1814 and is located in Lexington’s Gratz Park neighborhood. John Wesley Hunt was the first millionaire west of the Allegheny Mountains. Henrietta Hunt, John Hunt Morgan’s mother, inherited the home. Although it was his mother’s home, John Hunt Morgan never lived here.

The statue of General Morgan was erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1911. New York sculptor Pompeo Coppini believed that “no hero should bestride a mare,” so he sculpted Morgan atop a stallion. Morgan’s horse, Black Bess, was not.

These two sculptures are located at Cheapside, the site of one of the South’s largest slave markets. Here, families were torn apart. Wives were separated from their husbands; children torn from the arms of their mothers. And, there can be no doubt, slaves owned by the Breckinridge and Hunt-Morgan families were sold on the very ground now memorializing these two men who rose up in arms against the United States.

The Military Commission

The Kentucky Military Heritage Commission was established in 2002 and is charged with “maintaining a registry of Kentucky military heritage sites and objects significant to the military history of the Commonwealth.” Sites accepted onto the registry “cannot be damaged or destroyed, removed or significantly altered, other than for repair or renovation, without the written consent of the commission.”

The commission consists of the Adjutant General, the State Historic Preservation Officer, the Director of the Kentucky Historical Society, the Director of the Commission on Military Affairs and the Commissioner of the Department of Veteran’s Affairs.

Both the Breckinridge and the Morgan monuments are included on the registry. As a result, their removal, destruction, or alteration, must have the written approval of this Commission.

By the Numbers

The registry of sites under the purview of the Kentucky Military Heritage Commission, as of January 2016, is available online (Word file). According to the KMHC, there are 230 “eligible” military sites and objects eligible for inclusion on the commission’s registry; only 25* sites or objects, however, are listed.

[* There actually is a little confusion as it pertains to the registry index. At the beginning of the report, there are total listings by county and a separate listing by war/conflict. According to the former list, there are 25 listings on the register which the latter list suggests 27. As I count the total listings, I count 27. Meanwhile, the war/conflict total list suggests 14 Civil War sites, while I only count only 12 as provided in the graphic below.]

Among eligible sites/objects, 113 (49%) relate to the Civil War while 52% of sites on the KMHC registry relate to the Civil War. An overwhelming share of these pay homage to those who fought against the United States of America. (It’s worth noting that there are 0 sites/objects recognized as eligible from the War of 1812 despite the fact that 83% of military age Kentucky males served in the conflict fielding 36 regiments for the cause. Further 570,000 of saltpetre was mined out of Mammoth Cave and used in the war effort. Yet, no eligible sites or memorials?)

In Fayette County, there are 11 sites/objects identified although only 4 appear on the registry. Those four are the Breckinridge Monument, the Morgan Monument, the Confederate Soldier Monument (erected 1893), and the Confederate Monument (Ladies Memorial) (erected 1873). In other words, all 4 sites/objects on the registry (1) relate to the Civil War and (2) memorialize Confederate causes or individuals.

It cannot be ignored, by the nominations submitted to the Kentucky Military Heritage Commission have historically been more about the preservation of Confederate/Lost Cause history than anything else.

Of the 12 Civil War related sites/objects on the registry, 10 are connected to the Confederacy. That’s 83%. Now, keep in mind the following: Kentucky never seceded from the Union (we were, however, a house divided). Both Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis were born in Kentucky. More Kentuckians fought and died for the preservation of the Union than did for her destruction.

Telling History’s Story

Some have suggested that the removal of the statues in Lexington and across the country is a revision of history. I would argue to the contrary; the history memorialized by the Morgan and Breckinridge monuments does not properly tell of what truly transpired. What is more, it is a glorification of the worst among us. Furthermore, the history contained in these monuments is, itself, a revisionist history.

In the introduction to Creating a Confederate Kentucky, Anne Marshall quotes Kentuckian Robert Penn Warren, “When one is happy in forgetfulness, facts get forgotten.” The horror that Morgan poured out upon the Commonwealth was forgotten in favor of a perception of a genteel South and a noble cause. Marshall went on to write:

The conservative racial, social, political, and gender values inherent in Confederate symbols and the Lost Cause greatly appealed to many white Kentuckians, who despite their devotion to the Union had never entered the war in order to free slaves. In a postwar world where racial boundaries were in flux, the Lost Cause and the conservative potluck that with it seemed not only a comforting reminder of a past free of late nineteenth-century insecurities but also a way to reinforce contemporary efforts to maintain white supremacy.

In discussing the unveiling of the Morgan statue, Marshall wrote:

There was no outward sign of public objection to the man who had brought destruction to so many civilians during the war and no mention of the irony that the state on which he had inflicted so much damages and the state whose people he had robbed of thousands of dollars in species and horseflesh had spent many thousands more to honor him.

James Klotter also examined Kentucky’s nostalgic shift toward embracing the Lost Cause in his book Kentucky: Portrait in Paradox 1900-1950. He wrote that in the final decades of the 1800s, “Kentucky turned more and more sympathetic to the Lost Cuase.” Klotter noted that in 1902, a Confederate Home was built for Southern veterans and funds were appropriated for Confederate graves at Perryville. In 1910, the state legislature appropriate funds to the United Daughters of the Confederacy for the completion of the Morgan statue now at issue. In 1912, the state purchased the birthplace of Jefferson Davis. In 1926, Robert E. Lee’s birthday became a state holiday (and its not the only Confederate state holiday we celebrate in Kentucky).

Wrote Klotter,

Ironically, Kentucky had no need for a religion based on the Lost Cause, nor for a way to overcome the psychology of a tragic defeat – as did southerners generally – because most Kentuckians, and the state itself, had been on the winning side. Yet, they wholeheartedly embraced the mythology and the moonlight and magnolia image.

Much of the rewriting of history occurred in the waning years of the 19th century and the opening decades of the 20th century. The present discussion on removing the statues is not an attempt to hide history, but to tell a more complete and honest version of America’s history.