Used for centuries in England, the system of describing land by its metes and bounds is a common way of describing an area of land. Surveyors and other professionals utilize the system to specifically identify parcels of land though errors by the early surveyors creating much trouble in the early days.

Even with today’s surveys being done largely with technological advantage, it is possible for a call to be reversed and the wrong parcel be conveyed or mortgaged. The system of measured, however, is best understood by looking at the historic nature of how Kentucky itself came into being.

The Virginia Charters

In preparing for a presentation on the history of Lexington, I reviewed an online timeline of Fayette County. I’ve referenced this timeline before. It is a useful resource, but I questioned its first referenced fact when it suggested that the first Virginia charter (1606) included the territory that would become Kentucky.

|

| Southern States of America, 1909. Available here. |

Letting curiosity get the best of me, a quick Internet search offered a map of King James’ grants to the Plymouth and London Companies in 1606. As I suspected, they didn’t include the lands that would become Kentucky. A website called Virginia Places explained that the London Company “shall have all the landes, soile, groundes, havens, ports, rivers, mines, mineralls, woods, marishes, waters, fishinges, commodities and hereditaments whatsoever, from the firste seate of theire plantacion and habitacion by the space of fiftie like Englishe miles.“

Additionally, the First Charter offered a company 100 miles inland from its first settlement. But 100 miles won’t reach Kentucky.

In 1609, the Second Charter extended rights of the Virginia Company to all lands within 200 miles to the north nad south of the James River. It also gave to the Virginia Company what was then unknown to be such a massive offering:

we do also of our special Grace… give, grant and confirm, unto the said Treasurer and Company, and their Successors… all those Lands, Countries, and Territories, situate, lying, and being in that Part of America, called Virginia, from the Point of Land,from the pointe of lande called Cape or Pointe Comfort all alonge the seacoste to the northward two hundred miles and from the said pointe of Cape Comfort all alonge the sea coast to the southward twoe hundred miles; and all that space and circuit of lande lieinge from the sea coaste of the precinct aforesaid upp unto the lande, throughoute, from sea to sea, west and northwest; and also all the island beinge within one hundred miles alonge the coaste of bothe seas of the precincte aforesaid. (emphasis added)

From sea to sea, eh? In these pre-Lewis & Clark days, there was still little concept of just how wide the continent truly is. The boundaries of Virginia evolved over the next century-plus before settling on the more familiar lines when, in 1784, Virginia ceded claims to northwestern lands to the U.S. government. At this point in history, Virginia consisted of the modern states/commonwealths of Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Virginia: Breaking Up is Hard to Do

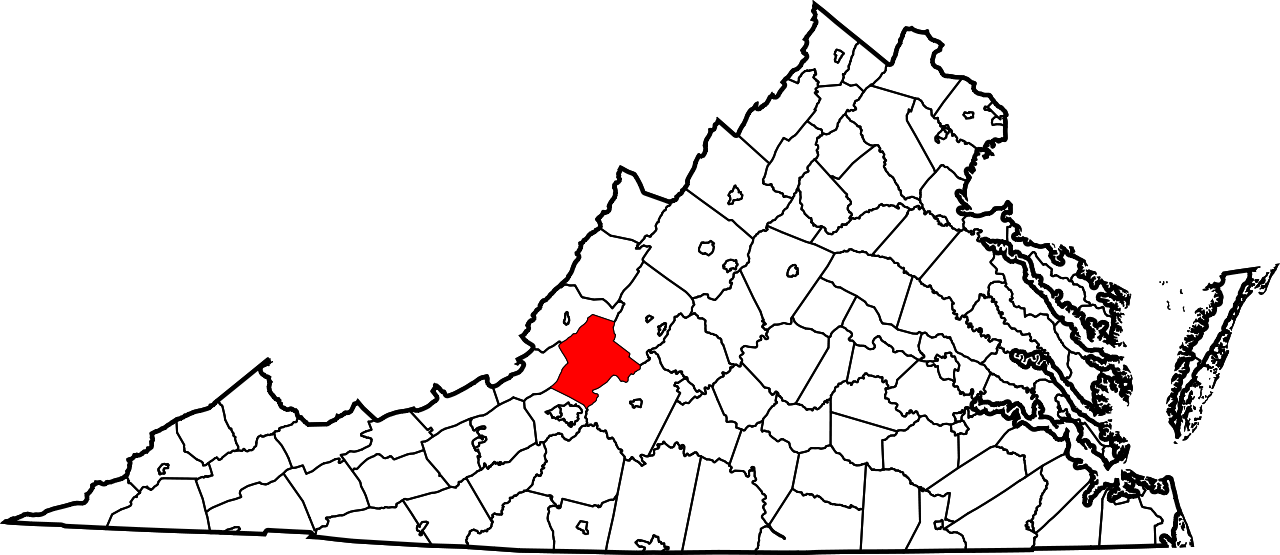

|

| The remaining Botetourt County, Virginia. Public domain. |

Kentucky arose from a still-extant Virginia county: Botetourt County which has been massively carved up over the centuries. Botetourt County was created in 1770, but the area that would become Kentucky was extracted in 1772 to become a portion of Fincastle County.

Fincastle County, which existed only through the conclusion of 1776, was carved up into three counties: Washington County (now exclusively part of Virginia), Montgomery County (which included parts of present-day Virginia and West Virginia), and Kentucky County.

Dr. Thomas Clark wrote, quoting Thomas Jefferson, that “obtaining justice should be made safe and easy as possible to all citizens.” It could be said that one reason for our declaration of independence from King George III was to achieve that dream of safe and easy justice. Of course, nothing about achieving justice has come with safety or with ease. Despite the challenges, shedding the chains of tyranny has become an American battle cry. This question framed the debate at our nation’s founding. And it framed the debate for Kentucky’s ultimate statehood.

|

| Secretary of State. |

Kentucky County survived only until 1780 when it was replaced by Jefferson, Fayette, and Lincoln counties. There was, at the time, a separate land claim for part of this area: Transylvania.

Transylvania Rises and Falls

Richard Henderson, a North Carolinian, led the Louisa Company (rechartered as the Transylvania Company) to secure the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in a land purchase from the Cherokees. The treaty was signed on March 17, 1775, and could have given rise to the State of Transylvania, but these claims were disputed. Much of the land lied in the portion of Fincastle County that would become Kentucky County.

In 1778, Virginia invalidated all title to land arising through the Transylania Company. North Carolina followed suit in 1783. In the interim, the national government sought to clarify the boundaries in the territory northwest of the Ohio River.

To these ends, Virginia gave up its land claims in this area on January 2, 1781, but it also required Congress to take several actions including the affirmation of Virginia’s boundaries and the claims of her citizens within that area. Further, Virginia required that all other claims arising from arrangements not ratified by Virginia (read: the Transylvania Company) would be rejected.

In the end, the State of Transylvania would not rise with its validity being rejected by Virginia, the United States, and even North Carolina.

1792 and beyond

On June 1, 1792, Kentucky was admitted to the Union with the permission of the Commonwealth of Virginia. At the time, there were eight counties. Today, there are 120 counties.

The division of Kentucky’s territory into counties has not been without controversy either. Just as the separation of America from England and Kentucky from Virginia were precipitated by the need for local governance, so too was the case with the creation of many of Kentucky’s counties.

In 1798, the residents of Marble Creek labored “under great inconveniences from their detached situation from their present seat of justice.” They sought the creation of a new county. From their efforts spawned by a dispute with the leadership in Fayette County, these Jessamine Countians carved a territory Fayette.

And beginning around 1900, the people of western Carter County around Olive Hill did not appreciate the 30 or 40 mile journey to the county seat of Grayson. Olive Hill was becoming populous given the fire brick industry developing in that portion of the county. And political disputes also suggested a division. On February 9, 1904, the governor signed into law the formation of Beckham County out of portions of Carter, Elliott and Lewis counties with Olive Hill being designated as the new county seat.

Beckham County needed revenues and issued tax bills to her citizens. Mr. Zimmerman, once a resident of Carter County, challenged his $75 bill. Carter County, defending her tax base, joined with Mr. Zimmerman to challenge the constitutionality of Beckham County which was soon out of existence.

Though the name wouldn’t be known for a significant portion of the epoch, Kentucky’s geopolitical and cartographic history spans more than four centuries. Today, the boundaries are governed by Chapter 1 of the Kentucky Revised Statutes – statutes which reference U.S. Supreme Court decisions decided as late as the 1980s. And within these boundaries, Kentucky has been divided into public and private lands.

Surveyors and others have called the points which would make these divisions. Since 1983, the state legislature has authorized the use of GPS coordinates in addition to the metes and bound system which has added accuracy to the whole system.

Yes, the “sun shines bright on my old Kentucky home” as measured from the “stone at the seven pines” and beyond.