|

| George H. Bowman House – Lexington, Kentucky. Author’s collection. |

An earlier version of this post appeared on this site in 2013 in what was, in reality, an early version of #DemolitionWatch. Based on a zoning change request, this structure had a lot of charm and appeal. But now the demolition permit was sought last week (October 20, 2015) for the old house at 4145 Harrodsburg Road. The land, which backs up to the Palomar subdivision, will be absorbed into that residential area.

In the spring of 2013, I spotted a sign in front of 4145 Harrodsburg Road indicating that a zoning request for the parcel would be from R-1D to R-1T. I rode onto the property, site of an abandoned home, to investigate further.

As it turns out, the residence was the George H. Bowman House, a ca. 1860 Greek Gothic Revival according to the Kentucky Historic Resources Survey conducted on the property in 1979.

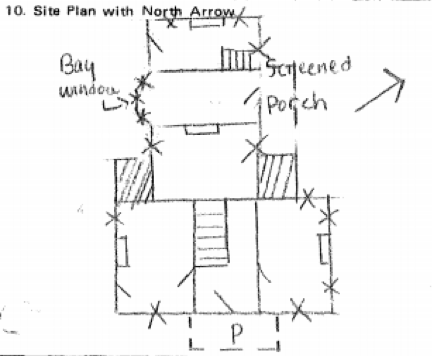

|

| Layout of Bowman House (Source: Resources Inventory) |

Property owners, according to early county maps, identify the owner in 1891 as John McMeekin who was the son of Jeremiah McMeekin. The elder was a butcher who had purchased Helm Place in 1873.

The owner in 1871 was J. S. Burrier, originally of Jessamine County, who acquired the home and 165 acres that year. He was married to Alice Craig, daughter of Lewis and Martha (Bryant) Craig.

It is believed that George H. Bowman constructed this house ca. 1860, though he remained only a few years. After inheriting Helm Place from his father, pioneer Abraham Bowman, George H. was forced to sell much of his inheritance to satisfy a gambling debt.

A. J. Reed took advantage of the younger Bowman’s misfortune and acquired the Helm Place property in 1859. It is believed that our subject house was built for George’s occupancy after the liquidation of Helm Place. Within the decade, George H. Bowman had passed away and his children divided and sold their father’s property.

Back to the present. The zoning change mentioned permitted the demolition of the Bowman House and the erection of four townhouse units in its place. It is worth noting, however, that the data relied on in the Map Amendment Request (MAR) included inaccurate data from the Fayette County PVA office.

The existing house was build in 1940, according to PVA records. Unfortunately, since the grant of the previous zone change (and prior to the purchase by the applicant) the house has fallen into a state of disrepair. There are structural issues relating to the foundation. Also contents and mechanical systems of the house have been torn out by unknown persons. Exterior decay issues are present. For all these reasons, it is impossible to preserve the house. (MARV 2013-3 Amd.pdf)

I truly doubt that preservation was an impossibility. Impracticable, perhaps. But not impossible. Several additional references existed in the MAR to the “1940 house.”

I was glad to have snapped these pictures before the old Bowman House was demolished. (I’m assuming demolition has occurred – any updates to the project?)

|

| George H. Bowman House – Lexington, Kentucky. Author’s collection. |

|

| Interior George H. Bowman House – Lexington, Kentucky. Author’s collection. |